In this detailed and illustrated analysis of Shakespeare’s sonnet 30, you’ll learn:

- How it is structured

- What it really means

- How Shakespeare uses language to deliver his message effectively

I’m Tutor Phil, and if you’re really curious what this sonnet means, here’s the short answer:

In sonnet 30, Shakespeare complains that the thoughts of past losses, unfulfilled desires, and old insults bring him suffering. But once he thinks of “you,” his friend and subject of this sonnet, all the pain is relieved.

Let’s dive into our analysis and see how Shakespeare forms a powerful argument and drives it home by means of brilliant poetry. First, we should read the sonnet:

Sonnet 30 by William Shakespeare

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste: Then can I drown an eye, unus'd to flow, For precious friends hid in death's dateless night, And weep afresh love's long since cancell'd woe, And moan th' expense of many a vanish'd sight; Then can I grieve at grievances foregone, And heavily from woe to woe tell o'er The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan, Which I new pay as if not paid before. But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, All losses are restor'd, and sorrows end.

(source: The Poetry Foundation)

How to Analyze Shakespeare’s Sonnets

An analysis of a Shakespearean sonnet consists of three phases:

- Uncover the overall, “big picture” structure

- Uncover the deeper structure, the less visible organization

- Examine the poetics – how the language helps to drive meaning

Phase 1 – The Main Structure of Sonnet 30

First, let’s take a look at what an analysis really is.

To analyze a work of literature means to:

- Break it into parts

- Study the relationships among the parts

- Arrive at the big, unifying idea

The unifying idea can be an argument or a theme that can usually be expressed in one sentence.

Armed with this definition, we’re ready for Phase 1 in which we want to uncover the main structure. To do that, we need to find two things:

- The main stated argument

- The main sections (usually two)

1. Uncover the main stated argument

When analyzing Shakespeare’s sonnets, note that he is very precise in his thinking. His poetry is not just descriptions of beautiful images and passionate feelings.

Shakespearean poetry, much like all the poetry written before the end of the 18-th century, is argumentative.

This means that we should look for an argument, an intellectual point, rather than for pretty images and emotions.

We’ll take a closer look at these elements, called poetics, later in the analysis. But our first task is to identify an argument Shakespeare makes, which he always does.

We can usually find the answer in the first quatrain (four lines of poetry). That’s where Shakespeare usually reveals the main underlying idea to the reader.

Let’s take a look at the first stanza of sonnet 30:

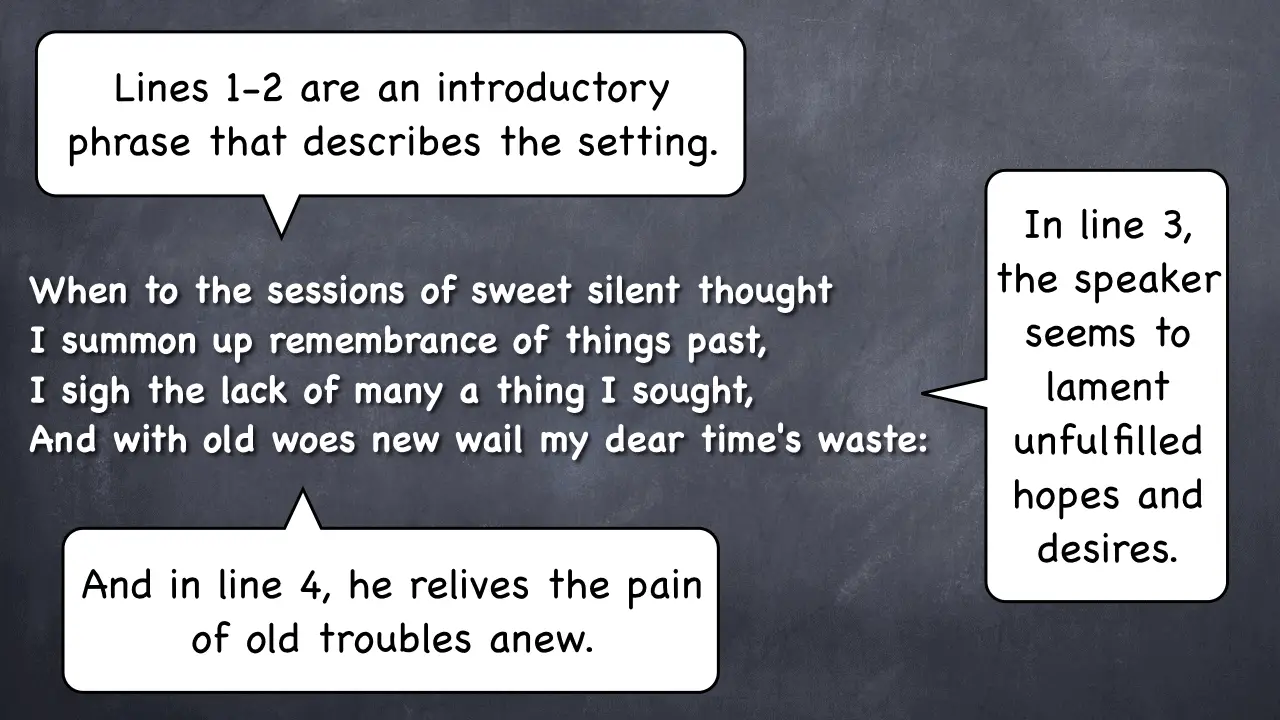

First, we notice that the first two lines are an introductory phrase, which is a part of a sentence that answers such questions as:

- Where?

- When?

- Under what circumstances?

Shakespeare sets the stage for the argument.

When does the action happen? It happens when he thinks quietly.

Where does it take place? It takes place in his mind.

Where does his mind go? It goes into the past.

And next, in lines 3 and 4, Shakespeare reveals his main argument:

In line 3, he’s lamenting things that he desired but couldn’t get. How do we know that? Well, we just need to read line 3 carefully.

The speaker does not lament a loss because in order to lose something, you need to possess it first. But he states that he “sought” those things yet he still lacks them. He does not mention having them – only having desired them.

In line 4, the speaker laments that he has to experience the pain of old wounds over and over again.

The subject of line 4 is pretty general. It is simply any pain associated with the past. It could be loss, unfulfilled desire, or any other kind of emotional pain.

We can now summarize the main argument as presented in the first quatrain:

“Thoughts of past unfulfilled desires and other troubles cause me pain.”

Now, is this argument complete? As we’ll see later in the sonnet, this is the main part of the argument, but it is not complete. The remaining part of the argument is revealed later.

To find the rest of the argument, we need to look for a key word. Usually, the overall argument contains some kind of a reversal, or a “turn.”

This is why we should look for a key word, such as:

- “Therefore” and its equivalents (so, thus, hence, etc.)

- “And” and its equivalents (also, too, etc.)

- “But” and its equivalents (however, nevertheless, yet, etc.)

Shakespeare usually begins a new section or new part of the argument with one of these key words.

What is the key word in this sonnet that introduces a new section?

Note that we already have one such word – “and” in line 4. It signals the separation into things unfulfilled and other things that bring pain.

We have more instances of the key word “and” in quatrains 2 and 3. By relying on these words, we know that they signal a continuation of thought.

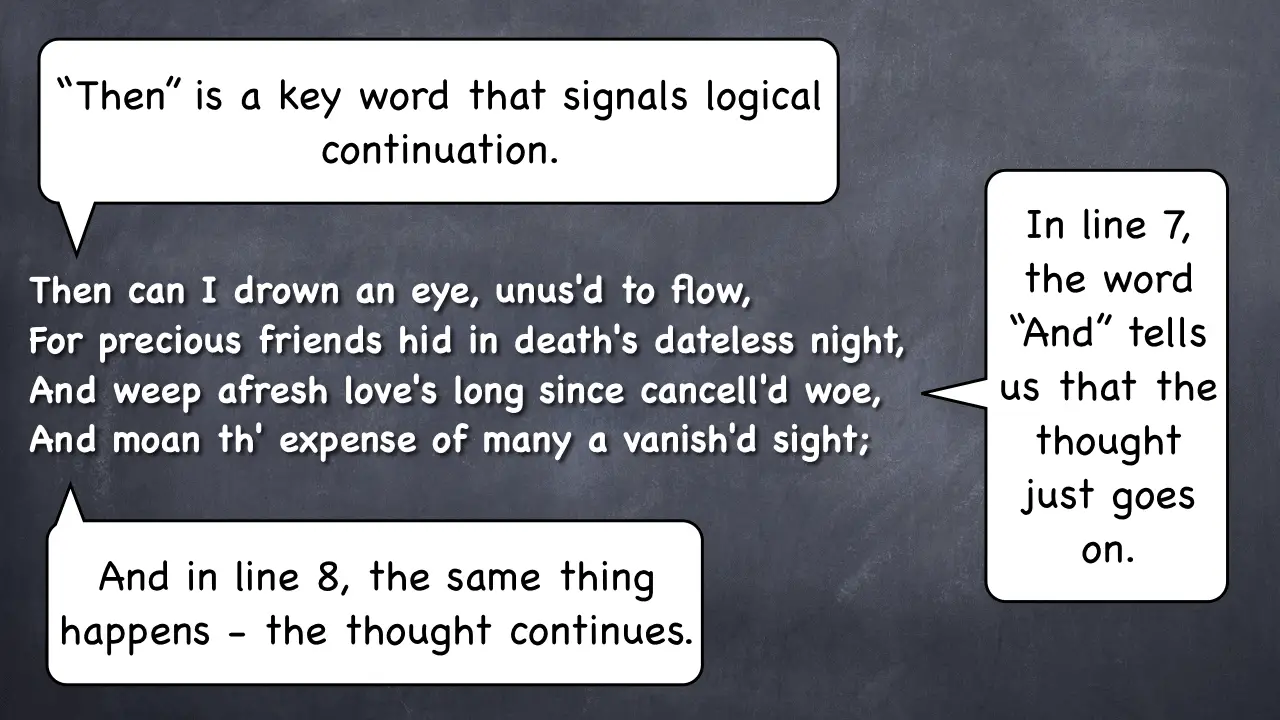

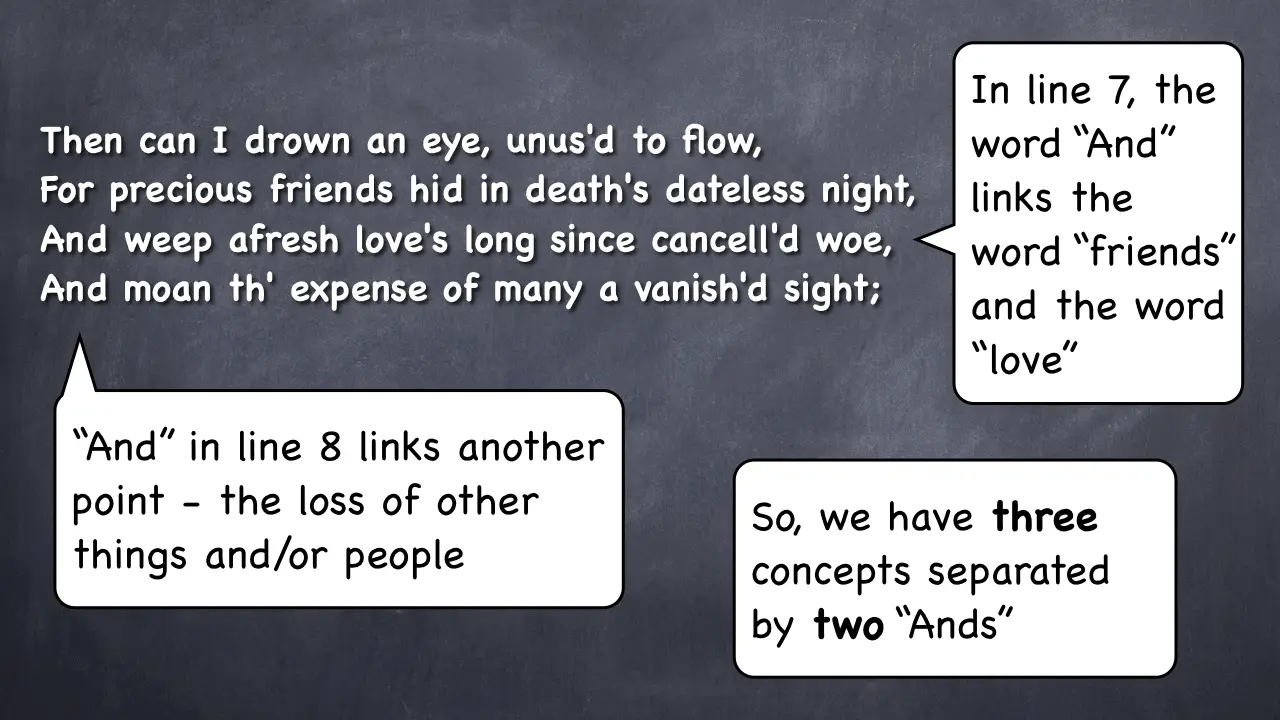

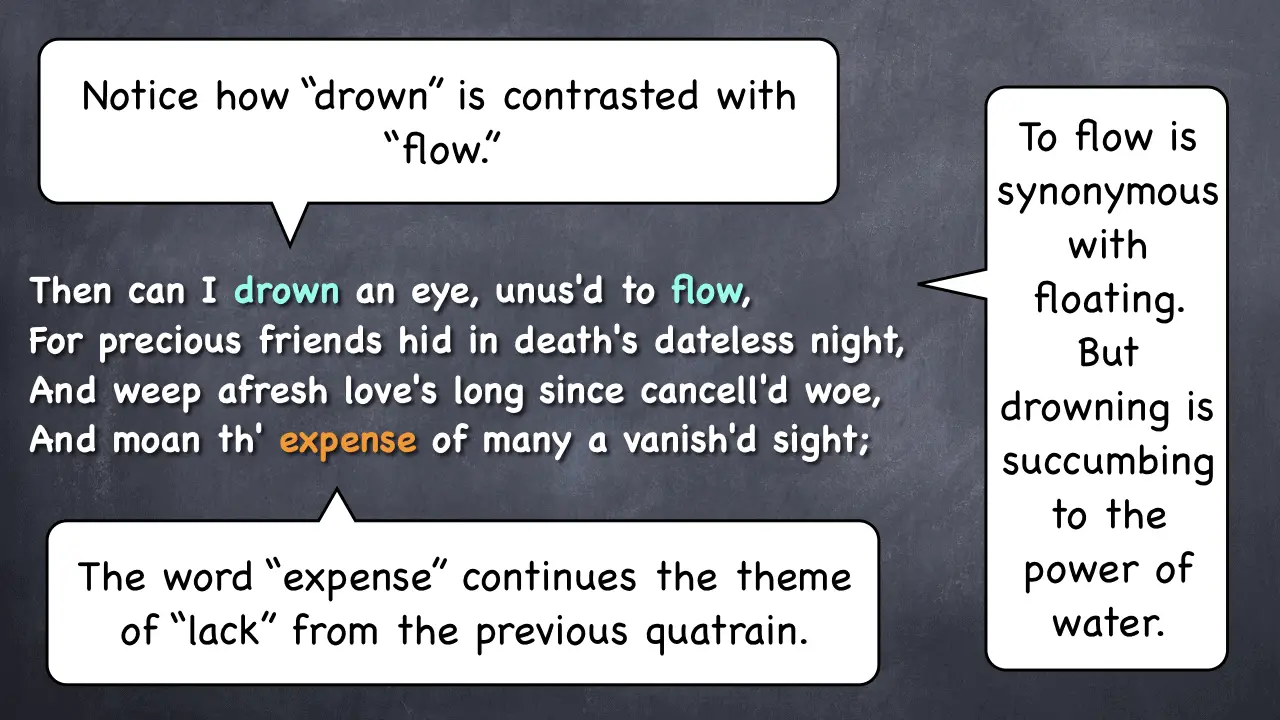

In fact, if we pay close attention, we’ll see that lines 1-12 are just one long sentence. Let’s take a closer look at the second quatrain (lines 5-8):

Why does Shakespeare start this quatrain with the key word “Then?” Because he started the whole sonnet with the introductory word “When,” which is also a key word.

To paraphrase, “When I think of the past, then I weep at the following things…”

In lines 7 and 8, the key word “And” helps Shakespeare expand his thought. We’ll talk more about this in a bit.

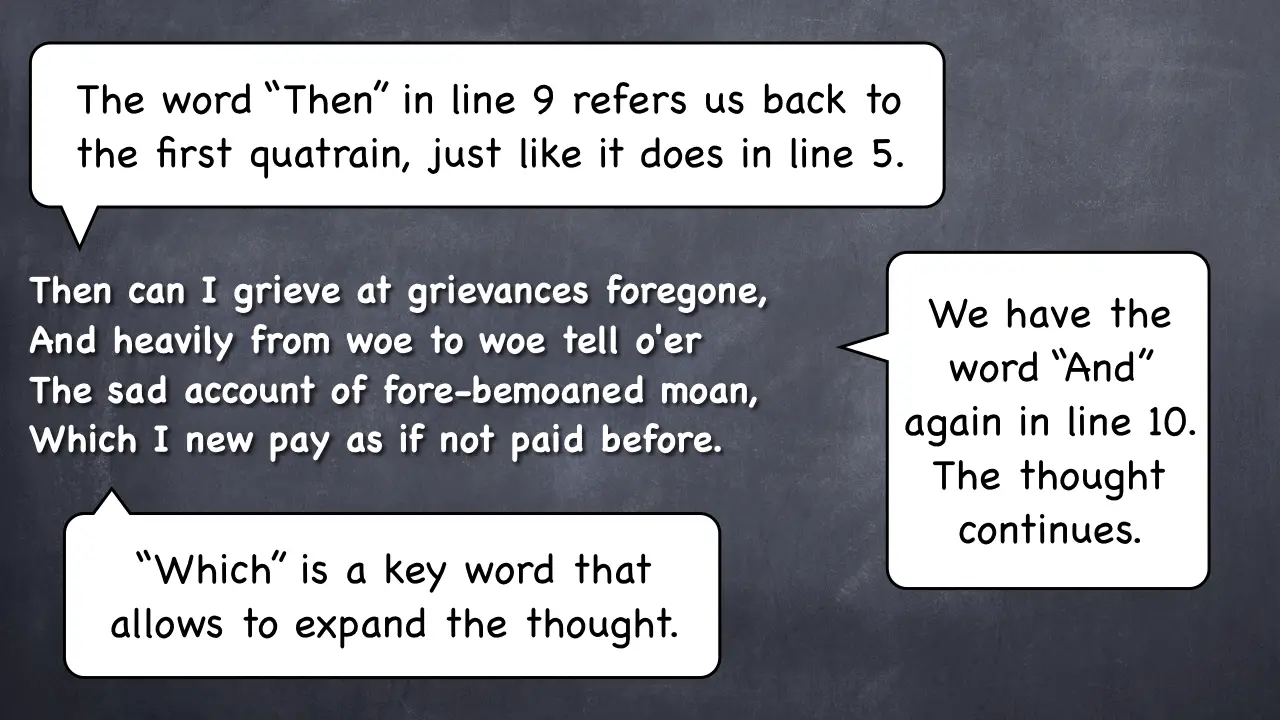

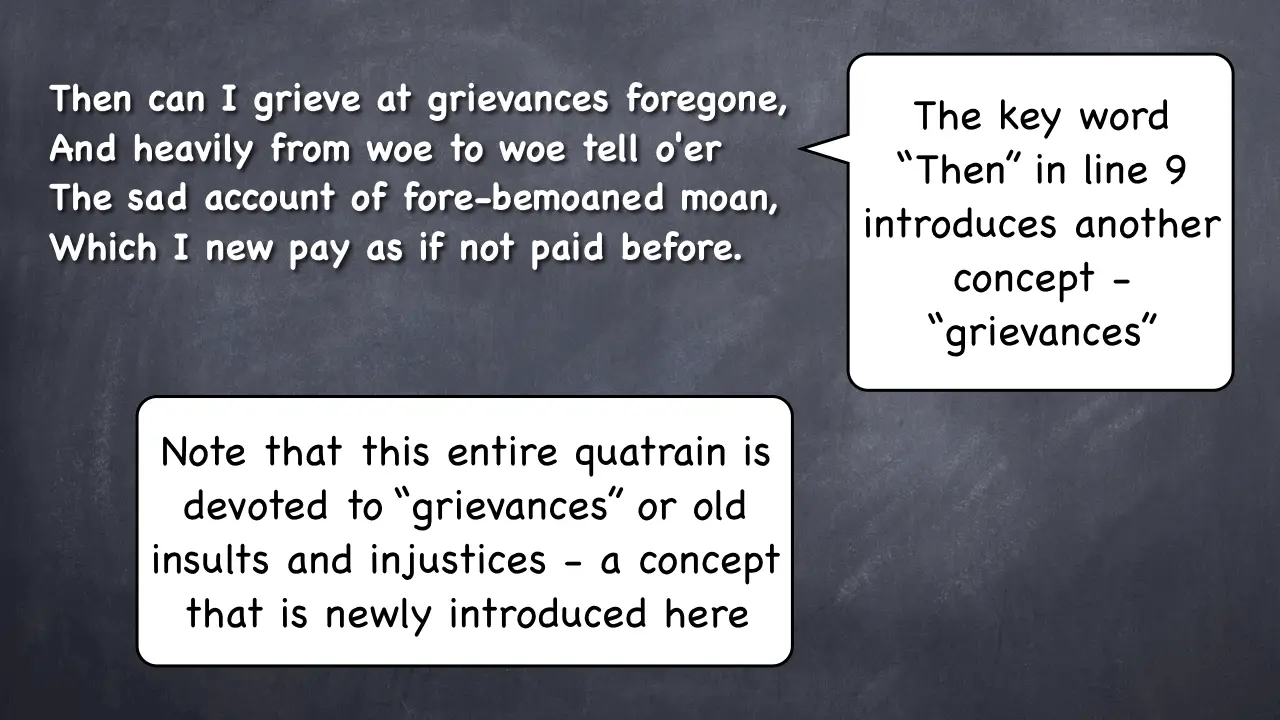

But now let’s take a look at the third and final quatrain (lines 9-12). (The last two lines of the sonnet, lines 13 and 14, are not a quatrain but a couplet.)

Can you guess why Shakespeare starts this quatrain with the word “Then” again? I think you guessed right. It’s because he picks up from the “When” in line 1 again:

“When I think of the past, then I weep at these things; then I also weep at those things.”

We have two more key words – “And” and “Which.” Both words enable Shakespeare to continue and expand his thought.

As I mentioned before, lines 1-12 are just one long sentence. The word “sentence” originates from the Latin word “sententia,” which means “thought.”

In other words, a sentence is a thought. And in this case, this is one long thought from Shakespeare which he puts together by using certain key words.

These words not only help the poet write the sentence – they also help the reader read and understand it.

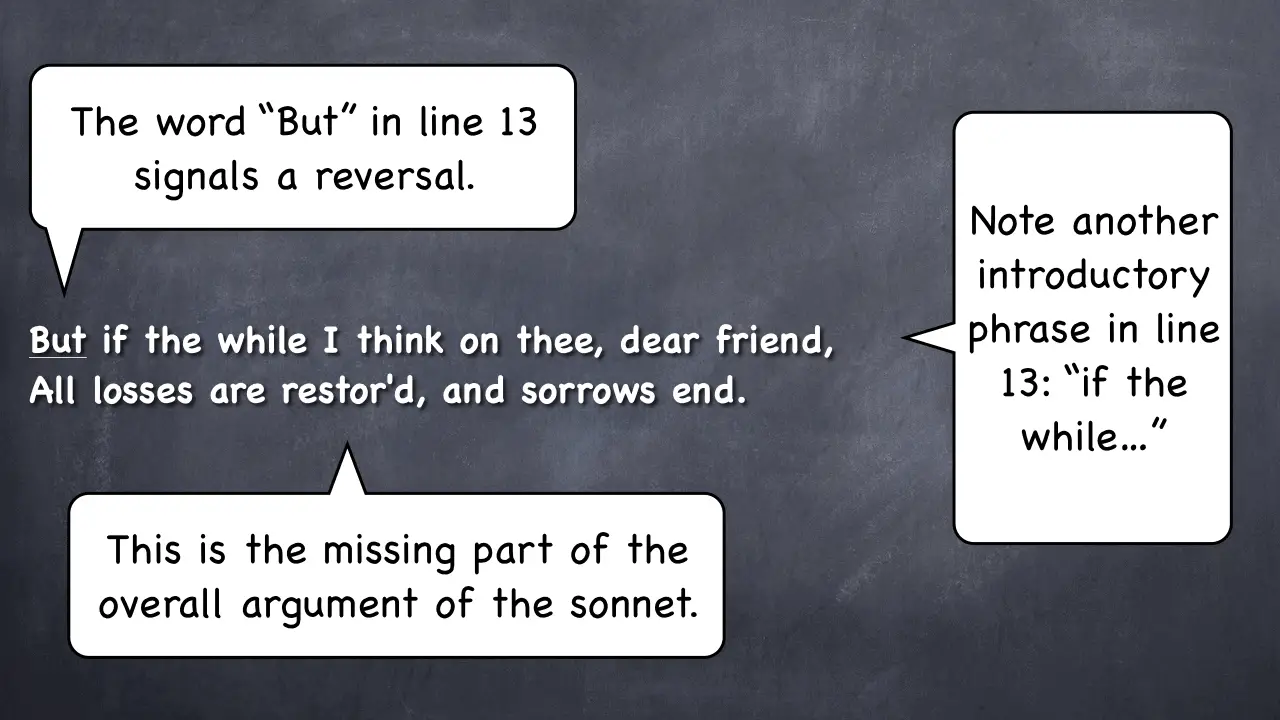

The Reversal

Now that we know that lines 1-12 constitute one thought, it’s time for us to look for a key word that would indicate a “turn” or a reversal.

A “turn” or a reversal will likely be introduced with a contrasting word, such as the word “But.”

And guess what – we have this word in line 13:

“But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,”

This word definitely signals a reversal. By the way, we have another introductory phrase that starts with the word “if.”

Note that the words “when” and “if” are synonymous. I can say, “When I think of you” or I can say “If I think of you.”

These statements are very similar. “When” implies time, and “If” implies a condition. But these words are pretty much interchangeable.

And thus we have identified the “turn.” What happens when the speaker “thinks on thee?” His pain goes away.

Up to now, we only had our main part of the overall argument. The missing part was the reversal. But now that we know the reversal, we can put together the entire argument, in summary:

“When I think of the past, all the unfulfilled desires and other troubles cause me pain; but when I think of you, all the pain disappears.”

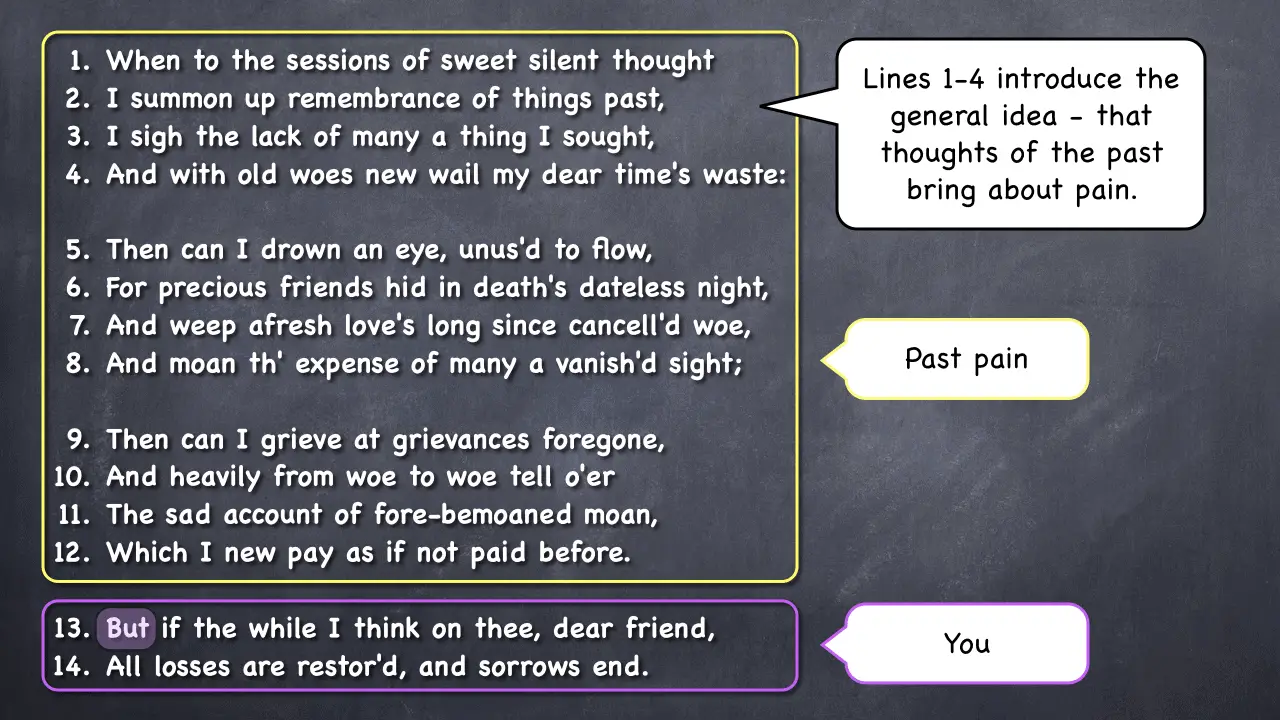

2. Uncover the main sections

Guess what – we have just figured out the entire sonnet’s main argument. Now, it’s time to “see” the structure.

And we can do this easily now that we have mapped it out roughly, using key words.

Clearly, we have two main sections.

Facts about the first section:

- It is contained in lines 1-12

- It is one complete sentence

- Its subject is the pain of the past

- It contains the first part of the overall argument

Facts about the second section:

- It begins in line 13

- It is introduced by the key word “But”

- Its subject is “you, dear friend”

- It contains the remaining part of the overall argument

Guess what – we’re done with Phase 1 of analyzing a Shakespearean sonnet. This is the most difficult part, really.

If you get the main argument and the overall structure right, the rest will be a lot easier. This has been the prerequisite. You can’t dig deeper into the sonnet unless you have the foundation Phase 1 gives you.

If you have to write an essay on this sonnet, what we’ve done so far can be enough to write a short essay. But if your analysis needs to be deeper, or if you have to write a bigger paper, then let’s dig in deeper and get you more material.

Phase 2 – Uncover the Deeper Structure

Our goal in Phase 2 is to try to reveal details that elude most readers and some of the best students.

We have found out how the sonnet works, for the main. Now we want to find out how each section works and if we can “read Shakespeare’s mind,” so to speak.

To do this, we must pay even closer attention to the poet’s words and phrases, including the key words.

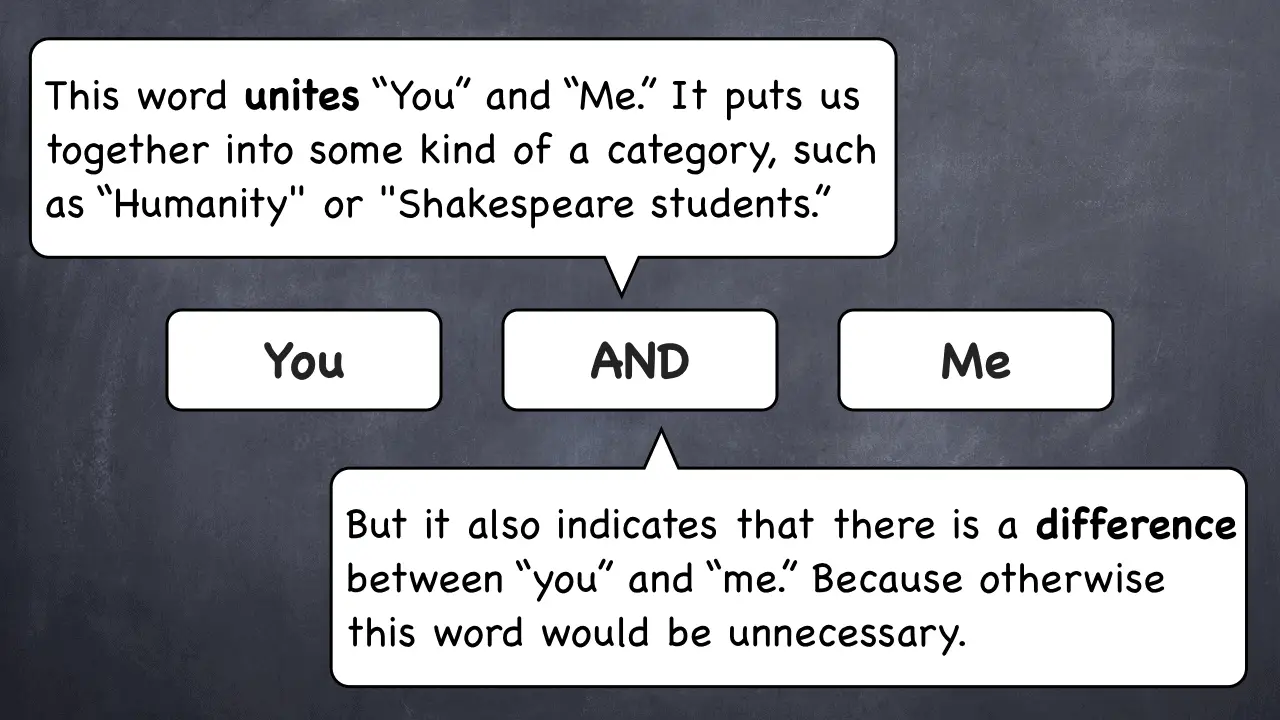

Here is something very important to understand about key words, such as conjunctions and transitional phrases. As you’ve probably noticed, they act like links that bind different parts together.

But here’s what’s interesting. Words that unite can also separate. Words that separate can also unite.

The key word “And” is a great example. Since Shakespeare uses it so often in this sonnet, we should take a closer look at it because that’ll help us conduct a deeper analysis.

Does this make sense? We should pay special attention to key words such as this one because they indicate some kind of a difference.

Remember:

We get a better idea of the structure of something when we identify its parts. And to do that, we must see the differences among the parts.

If we can’t tell the difference between two parts, we can’t even see the parts. They all seem like one block of text. Our vision is fuzzy.

So, let’s take a look at how the key word “And” as well as other key words can help us see a deeper structure and gather deeper meaning from this sonnet.

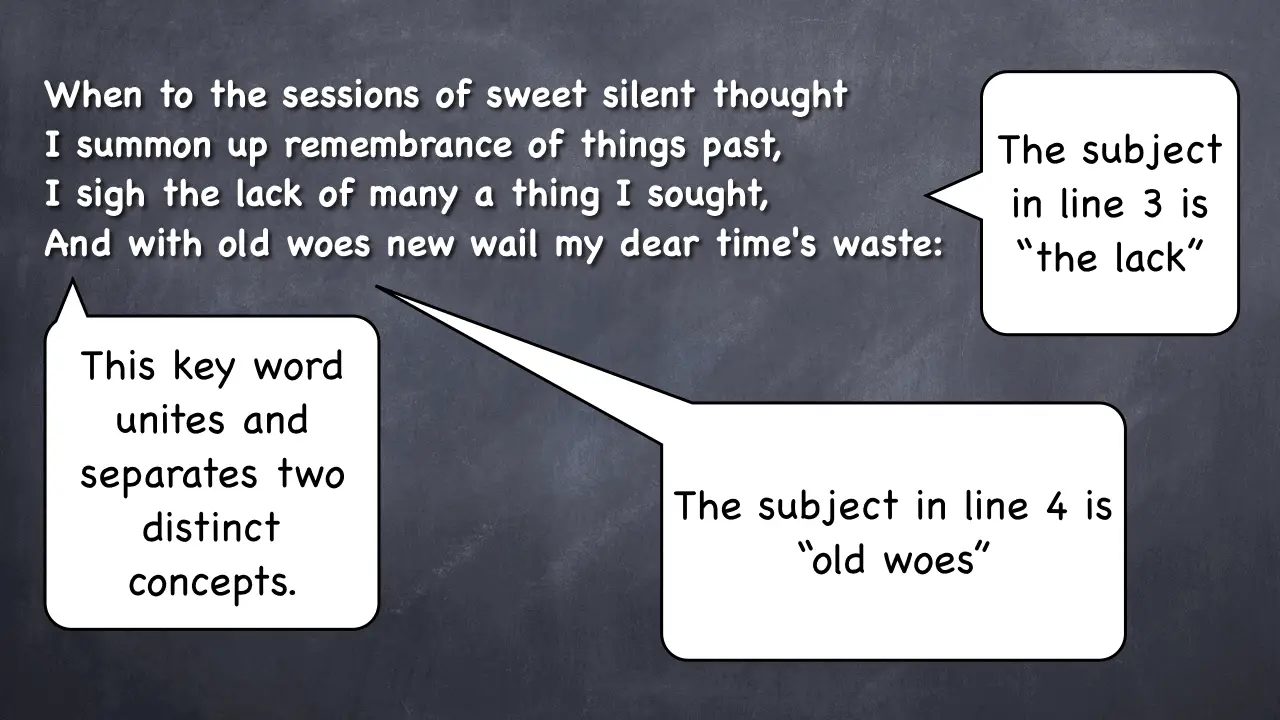

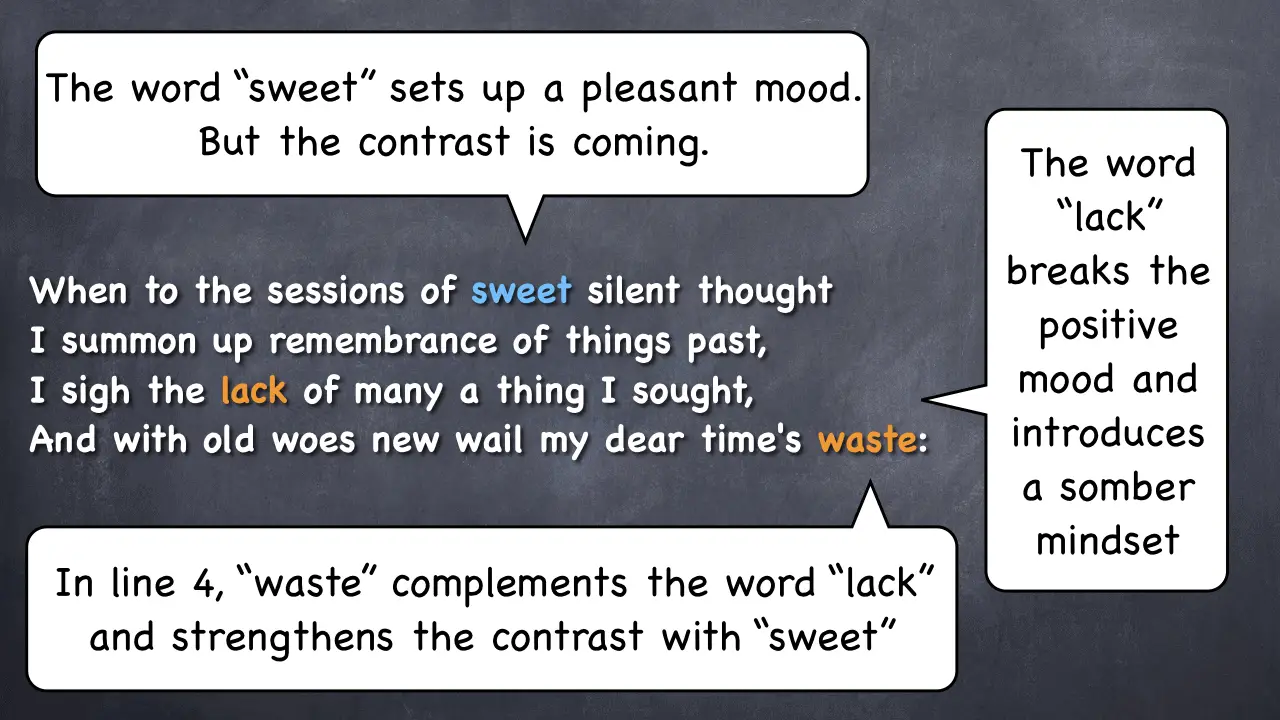

Quatrain 1 (lines 1-4)

We’re interested in lines 3 and 4 because Shakespeare introduces two distinct concepts here.

The first one is “the lack” in line 3, and the second one is “old woes” in line 4. What is the fundamental difference between the two?

The lack is more specific than old woes. In other words, “the lack” is one of the “old woes.”

“The lack of many a thing I sought” is a lamentation of unfulfilled hopes or wishes. That is a rather specific kind of an emotional pain.

Conversely, “old woes” can refer to anything. So, we are now looking for more specific concepts because they will fall into the category of “old woes” while providing us with a clearer picture of what exactly Shakespeare is lamenting.

Quatrain 2 (lines 5-8)

Lines 6 and 7 provide us with more specific information. In line 6, it is clear that the speaker is sad about his loss of old friends who have died.

This is a specific kind of a loss and is different from the feeling of unfulfilled hopes that we saw in the first quatrain.

In line 7, “love’s long since cancelled woe” can refer to one of three things. It can be breakups, unrequited love, or both.

So, this lamentation about love is not specific enough for us to know what exactly hurts the speaker. But it’s specific enough to know that these are pains associated with love.

Note that if Shakespeare is talking about unrequited love, then this falls perfectly under the category of “unfulfilled desires” mentioned in quatrain 1.

In line 8, is “the expense of many a vanished sight” specific or general? It’s rather general because it is the loss of people the speaker once knew.

This is more general than the loss of friends or pain related to love. This is also different from unfulfilled hopes or desires.

Quatrain 2 (lines 5-8)

In this quatrain, Shakespeare introduces a brand new kind of pain. And that is the memories of old grievances, which means old insults and any kinds of injustice committed against the speaker.

This kind of pain falls very well into the category of “old woes” brought up in quatrain 1. But it’s not a loss or an unfulfilled wish. This type of emotional pain is different from the others.

Finally, we already know the contents of the last two lines, the couplet. It is the reversal and the remaining part of the main argument. So, we’ll leave it at that.

As a result of digging deeper into the sonnet, we have a much more comprehensive view of its structure and meaning. We have a better understanding of it.

Let’s revisit our summary of Shakespeare’s overall argument:

“When I think of the past, all the unfulfilled desires and other troubles cause me pain; but when I think of you, all the pain disappears.”

We can now rewrite this summary to include new insights we just got by digging deeper into the sonnet:

“When I think of the past, all the losses, unfulfilled desires, and old heartache and insults cause me pain; but when I think of you, all the pain disappears.”

Now, we have a complete intellectual understanding of the sonnet. This summary is exhaustive. It doesn’t leave anything out.

When you write about a sonnet, you really want to get to this level of clarity because it will help you write a page after page of interesting and original content while staying true to the text.

Phase 3 – Examining the Poetics

Poetry, and Shakespeare specifically, offer no shortage of literary devices to discuss. But the reality of Shakespeare is that he was not an academic.

He was a working playwright, and his language was practical and accessible to kings and queens as well as to the common people of his day.

So, we won’t use complex technical terms here. All we need is to be perceptive.

Some of the most common literary devices Shakespeare uses are:

- Metaphors

- Similes

- Contrast

- Themes

Let’s look at some of these in sonnet 30.

Quatrain 1

Notice how Shakespeare begins softly and sweetly. This sets the reader up for a contrast that comes in line 3.

In fact, lines 3 and 4 introduce a theme of “lack” that continues to the end of the sonnet. And its undertone is financial. Shakespeare uses the theme of money and its scarcity to illustrate his emotional bankruptcy when he thinks of the past.

You’ll see how this works in the coming quatrains.

Quatrain 2

Here is another great example of a contrast. Notice how the speaker “drowns” in his sadness. He is “unused to flow,” which has two meanings.

The first meaning is that he is not used to crying. This is the literal, surface meaning.

But the unconscious association is created when the speaker “drowns” because he is unused to “flowing,” which is synonymous with floating.

In other words, the speaker can’t get used to this sadness and sinks every time he tries to swim in his thoughts of the past.

This is pretty brilliant, if you ask me.

And the last line of the quatrain contains the word “expense” which continues and reinforces the theme of financial lack.

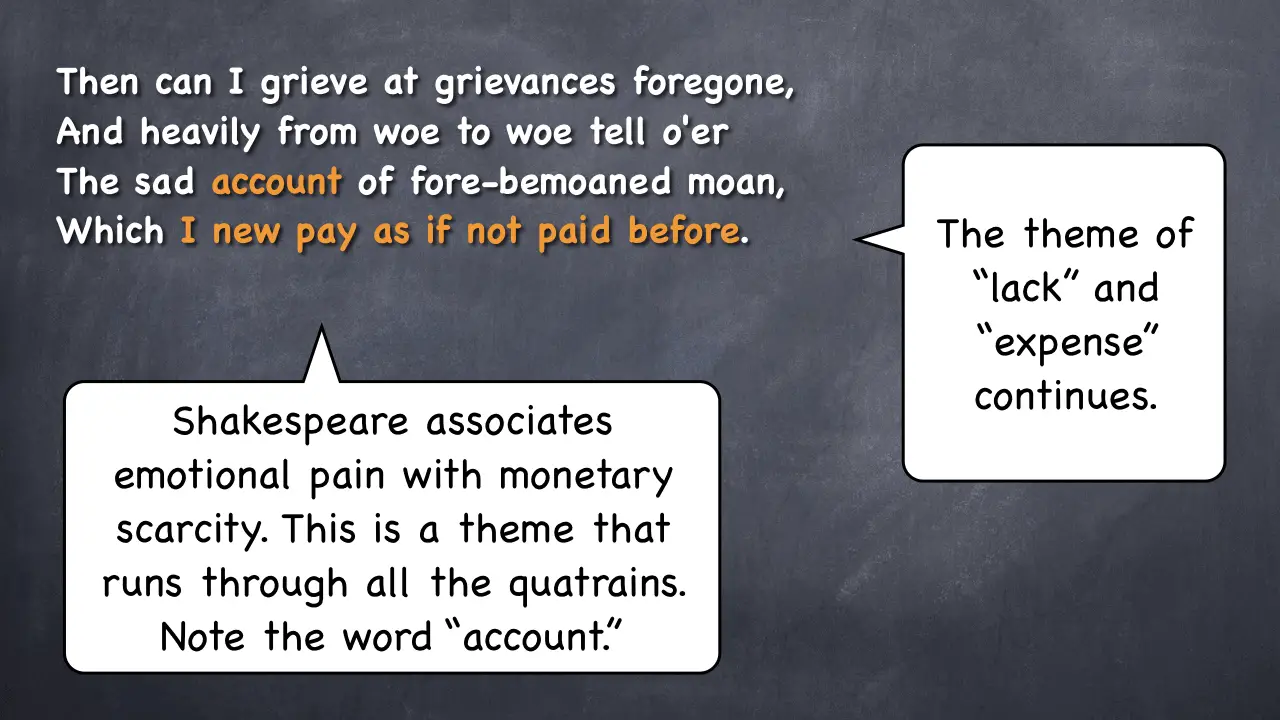

Quatrain 3

Now that we’ve talked a little about the theme of money and its scarcity, the language used in the last two lines of this quatrain speaks for itself.

The speaker keeps paying this old account as if it’s not paid off. Apparently, it’s not.

You could also argue that the word “grievance” in the first line is a legal term that refers to expression of conflict between an employer and employee. Such grievances usually involve wages in some way.

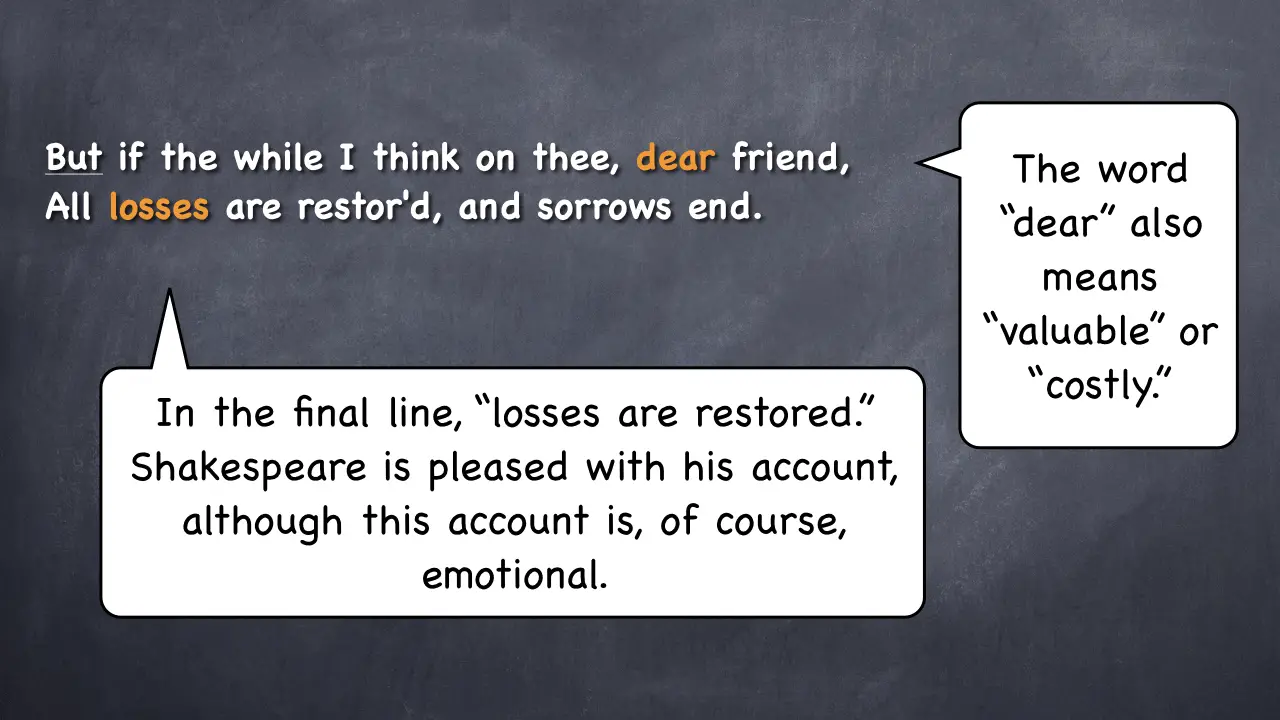

The Couplet

Finally, the “losses” are restored. The speaker’s “account” is in good shape again. And the theme of money and its scarcity has done its job.

Note the word “dear” in the first sentence. It connotes not only personal but also material value, if we consult with the dictionary. Hence the phrase: “to pay dearly.”

And we’re done with poetics. Shakespeare is a bottomless pit when it comes to figurative language. But let’s stop here.

At this point, you should have a very thorough understanding of this sonnet. You can also write a great paper or a really nice essay using this analysis.

I hope this was helpful. If you liked this analysis, you may like the one I did of sonnet 18.

If you have questions or comments, just post them below. And may your love of Shakespeare deepen and increase!

Tutor Phil